Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: health needs assessment

Published 9 September 2021

Applies to England

Applies to: England

Acknowledgements

Report author: Andrew Trathen, Public Health Registrar based at the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)

Contributors:

- Corin Barton, Senior Lecturer, University of Law

- Matthew Birkenshaw, Tobacco Control and Alcohol Labelling Policy Lead, Healthy Behaviours Team, DHSC

- Sandra Butcher, Chief Executive, The National Organisation for FASD

- Penny Cook, Professor of Public Health, University of Salford

- Andrea Duncan, Deputy Branch Head, Healthy Behaviours Team, DHSC

- Kate Fleming, Senior Lecturer in Social Epidemiology, University of Liverpool

- Raja Mukherjee, Consultant Psychiatrist, National Clinic for FASD

- Rachael Nielsen, Project Manager, Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies, Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership

- David Obree, Archie Duncan Fellow in Medical Ethics and Fellow in Medical Education, University of Edinburgh

- Róisín Reynolds, Senior Advisor, Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies, Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership

Executive summary

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) refers to the range of neurodevelopmental problems caused by pre-natal exposure to alcohol. The effects are diverse and impact on the individual throughout their life course.

This document is a health needs assessment for people living with FASD, their carers and families, and those at risk of alcohol-exposed pregnancies in England. It was written following a series of roundtable events in 2018, between the Deputy Chief Medical Officer (DCMO), and policy makers from DHSC, experts and people with lived experience. Developed in collaboration with a range of professionals around the country, it should provide an accessible and reliable source of information for those wishing to engage with the issue regardless of their background.

The needs identified for this population group focus on:

- a lack of robust prevalence estimates in England

- the importance of multi-sector working to support individuals through the life course

- better training and awareness for health professionals

- better organisation of services to improve accessibility

- a need to develop innovative approaches to support those living with the condition

Although there are few reliable sources of data to inform a strongly quantitative health needs assessment, this document takes a wide-ranging approach not only to identify areas where the needs of this population group are not being met, but to put this in context. For this reason, sections on policy, law and ethics are included as well as a section focussing on the voices of those affected by FASD. This document should be seen as a starting point for those wishing to learn more about the issue, and the reference list should be a useful tool for further reading.

Background

Introduction

FASD is a lifelong condition caused by alcohol exposure to the developing fetus. It can have a significant impact on early-years development and life chances. We do not have reliable FASD prevalence estimates for England, though individual studies, international data and some local studies give insight to the potential extent of the problem.

Prevention and awareness raising is being undertaken by Public Health England and NHS England and NHS Improvement, and responsibility for commissioning of services lies with clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) working across sectors. The government recognises the importance of FASD and funded 5 voluntary sector organisations to work on FASD from 2020 to 2021, as part of a broader programme helping children of alcohol dependant parents (CADeP).

This document is a health needs assessment focused on people living with FASD, their carers and families, and those at risk of alcohol-exposed pregnancies across England. It draws on primary sources from across the United Kingdom and internationally, and incorporates clinical, academic and policy expertise from stakeholders around the country.

It has been produced following a series of roundtable events in 2018 with the DCMO, which provided an opportunity for experts and people with lived experience to put forward their views at a national level. The needs assessment aims to provide an accessible summary of the current state of research and policy, present relevant data where available to explain the extent and types of health needs, and reviews current health systems and services. It should provide an accessible and objective information resource for policy makers and those with a personal or professional interest in the issue.

Alcohol consumption in the UK

FASD requires alcohol exposure during pregnancy to occur. Although we do not have up to date, accurate data on the number of alcohol-exposed pregnancies, data on general drinking habits across the population is routinely collected by the Health Survey for England, most recently from 2019.

This data shows that:

- 22% of women in England did not drink alcohol in the last 12 months

- 59% of women in England drank at levels within the UK CMOs’ low risk drinking guidelines (that is 14 units or less in the last week)

- 9% drank at an increasing risk level (14 to 35 units)

- 2% drank at a higher risk level (over 35 units)

The figures for women drinking more than 14 units per week varied across age groups, with age 55 to 64 the most common (20%).[footnote 1]

The best data available for the proportion of women who consume alcohol during pregnancy comes from the Infant Feeding Survey 2010,[footnote 2] though this has since been discontinued and guidance for pregnant women has changed. Nevertheless, 2010 data showed that: 2 in 5 mothers (40%) drank alcohol during pregnancy, which was fewer than in 2005 (54%). Mothers aged 35 or over (52%), mothers from managerial and professional occupations (51%) and mothers from a White ethnic background (46%) were more likely to drink during pregnancy. Mothers in England (41%) and Wales (39%) were more likely to drink during pregnancy than mothers in Scotland and Northern Ireland (35% in each).

A study in 2017 estimated alcohol consumption during pregnancy in different countries around the world, placing the UK 4th highest (41% drinking during pregnancy).[footnote 3], [footnote 4] The study does recognise significant limitations however, such as relying on people’s memory to record alcohol use, and inconsistent data on drinking patterns. A UK cohort study suggested a higher proportion (79% drinking in the first trimester, declining thereafter).[footnote 5]

Across all age groups, men are more likely to drink at increasing and higher risk levels. There is some data suggesting that alcohol may affect sperm and overall vulnerability to FASD. However, from a policy perspective alcohol consumption by men is important because prevention strategies aim to encourage the partners of pregnant women to reduce alcohol consumption. It is therefore important to acknowledge the relatively higher risk drinking patterns in men compared to women.

Biological effects of alcohol and the fetus

As the fetus develops in the womb, it is particularly vulnerable when exposed to substances that can affect its development. These substances are known as teratogens. Alcohol is a known teratogen,[footnote 6] but the science underlying its effects still continues to be developed.

What we do know is that alcohol can pass through the placenta and spread rapidly to the amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus. The alcohol is removed from the fluid far more slowly than the mother eliminates it from her own system, meaning that it accumulates. This creates a ‘reservoir’ of alcohol around the fetus, which will be swallowed and circulated in the fetus’ system. The fetus only has a limited ability to process, or metabolise, the alcohol compared to the mother, and so the effect is prolonged.[footnote 6] Multiple studies using animal models have shown that even low levels of alcohol exposure can lead to developmental abnormalities, at all stages of embryonic development.[footnote 7]

While some of the mechanisms of alcohol teratogenesis have been discovered, many also remain uncertain. However, we do know alcohol can have characteristic impacts on development that persist after birth and throughout life. These may include pervasive and long-standing central nervous system dysfunction in the following areas:

-

motor skills

-

neuroanatomy or neurophysiology

-

cognition

-

language

-

academic achievement

-

memory

-

attention

-

executive function, including impulse control and hyperactivity

-

affect regulation

-

adaptive behaviours, social skills or social communication

Source: SIGN 156, Children and young people exposed prenatally to alcohol, page 21

It may also include:

structural deficits and/or birth defects involving ears, eyes, palmar creases, digits, elbow, joints and heart… Children with FASD are also at increased risk of additional structural defects including congenital heart defects and orofacial clefts.

Source: SIGN 156, Children and young people exposed prenatally to alcohol, pages 69 to 71.

Individuals can experience a wide range of these problems, of varying degrees of severity. This depends on the timing, frequency and level of alcohol exposure; although we understand that higher levels of alcohol consumption increase the risk, the details of how development is affected continues to improve. There appear to be critical periods during the pregnancy where a given dose of alcohol will have a much more serious effect than if given at another time, but the exact timing when these critical periods are remains unclear. Even if this could be established, pregnant women would not know the precise stage of development of the fetus at a given point in time.[footnote 8] Therefore, although the evidence shows the level of risk changes during the pregnancy, current knowledge suggests that alcohol consumption at any stage of pregnancy presents a risk and should therefore be avoided.[footnote 5]

Some individuals affected by pre-natal alcohol exposure exhibit most of the issues listed above, alongside a set of facial characteristics that are recognisable by health professionals. This pattern of anomalies is referred to as FASD with sentinel facial features.

This can be diagnosed by the severe impairment in 3 areas of neurodevelopmental assessment plus the presence of 3 definitive facial features which can include the following:

- short palpebral fissure (small eyes)

- thin upper lip

- smooth philtrum (area between the mouth and nose)

Features such as a flat midface are characteristic but until now could not be easily measured as part of the core features, therefore are not included in routine non-specialist assessments. Other features are often associated. Associated features develop in early pregnancy and may not be seen in many cases, these include skin folds inner eye corner, low set pointed ears, short nose and small jaw (micrognathia) (see figure 1).

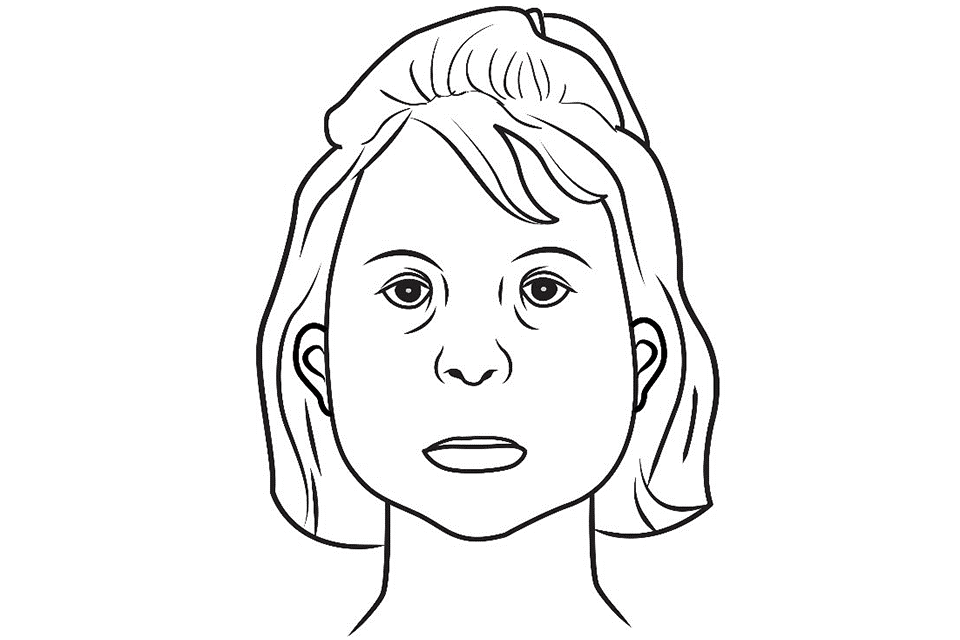

Figure 1: typical features of FASD with sentinel facial features

In more than 90% of cases the sentinel facial features are not present. The diagnosis is FASD without sentinel facial features. In a small proportion of FASD cases, less than 10%, some facial features are also present,[footnote 9] which can be described as ‘FASD with sentinel facial features’.

Prior to this change, there was an array of different terms, as described below. It is critical to understand that “A diagnosis of FASD is only made when there is evidence of pervasive brain dysfunction, which is defined by severe impairment in 3 or more of the following neurodevelopmental domains” ([footnote 10], p 21). There is no ‘mild FASD’.

FASD is linked to a range of other conditions known as co-morbidities, which necessitate access to a multi-disciplinary team for long-term support. A systematic review by Popova et al [footnote 11] identified 428 co-morbidities. Denny et al[footnote 12] provide examples that illustrate the wide range of potential effects (table 1).

Table 1: examples of co-morbid conditions associated with FASD (modified from Denny 2017)

| System | Condition |

|---|---|

| Brain and nervous system | Microcephaly, seizure disorder, spinal cord abnormalities, structural brain abnormalities (including corpus callosum, cerebellum, caudate, and hippocampus) |

| Digestive | Enteric neuropathy |

| Hearing | Chronic serous otitis media, conductive and/or neurosensory hearing loss |

| Heart | Aberrant great vessels, atrial septal defects, ventricular septal defects |

| Kidneys | Aplastic, dysplastic or hypoplastic kidneys, horseshoe kidney, hydronephrosis, ureteral duplications |

| Muscles and bones | Camptodactyly, clinodactyly, flexion contractures, hypoplastic nails, radioulnar synostosis, scoliosis, spinal malformations |

| Oral and facial | Cleft lip, cleft palate |

| Psychiatric and behavioral | Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, intellectual disability, language disorders, learning disabilities, mood disorders, oppositional defiant disorder, sensory processing issues, substance use disorders |

| Vision | Ptosis, retinal malformation, strabismus, visual impairment |

The neuro-developmental problems associated with FASD can create great difficulties for individuals in their childhood that persist throughout life. Impaired ability to learn, remember, make judgements and forward plan make day-to-day life very challenging. This results in problems at school, trouble with the law, substance misuse problems and risky or inappropriate sexual behaviours.

Effects throughout the life course

Effects of pre-natal alcohol are known to have lifelong consequences, though the impact this has on adolescents and adults is less well understood. Although some effects of FASD can improve over time, it is common for secondary disabilities to develop as a result of other problems. The cognitive deficits, behavioural problems, psychopathology and other secondary disabilities associated with FASD affect an individual’s ability to navigate their daily life and become independent adults.[footnote 13]

International studies illustrate the potential extent of the problem. Streissguth[footnote 14] looked at a range of adverse life outcomes in the US, and found that the life span prevalence was 61% for disrupted school experiences, 60% for trouble with the law, 50% for confinement (in detention, jail, prison, or a psychiatric or alcohol or drug inpatient setting), 49% for inappropriate sexual behaviours on repeated occasions, and 35% for alcohol or drug problems.

It should be noted that this study found a 2 to 4 fold reduction in the odds of developing these adverse outcomes if a diagnosis was made before the age of 12. Other studies have made similar findings.[footnote 15]

In Germany, a small 20 year study focussed on some of the most complex cases of FASD.[footnote 16] They followed 37 patients who showed very poor outcomes following a psychosocial and career interview. 18 subjects (49%) had received special education only, 14 (38%) had passed primary school, and only 5 (13%) had a secondary school education. By occupational status, only 5 subjects (13%) had ever held an ‘ordinary’ job. This is despite 69% having received some preparatory job training (albeit with 19% terminating this prematurely). Although the study participants were among those most severely affected, the study clearly highlights the extent of life-long social challenges that FASD can cause.

Alcohol consumption and pregnancy

FASD can only occur if alcohol is consumed during pregnancy, offering an opportunity for prevention where alcohol can be avoided.

An important component of any policy response to FASD should therefore include efforts to reduce the number of women drinking alcohol during pregnancy or while planning to be pregnant. Consistent with findings from other countries, there is evidence that the UK public have some awareness of FASD, although understanding of the risks of alcohol-exposed pregnancies remains superficial.[footnote 17]

In 2016 the CMO issued guidelines for lower risk level of alcohol consumption for men and women. This included specific updated advice that alcohol consumption should be zero for those pregnant or planning to be pregnant:

If you are pregnant or think you could become pregnant, the safest approach is not to drink alcohol at all, to keep risks to your baby to a minimum.

Drinking in pregnancy can lead to long-term harm to the baby, with the more you drink the greater the risk.

The risk of harm to the baby is likely to be low if you have drunk only small amounts of alcohol before you knew you were pregnant or during pregnancy.

If you find out you are pregnant after you have drunk alcohol during early pregnancy, you should avoid further drinking. You should be aware that it is unlikely in most cases that your baby has been affected. If you are worried about alcohol use during pregnancy do talk to your doctor or midwife.

Source: UK CMOs’ Low Risk Drinking Guidelines 2016

Publication of this advice in 2016 led to an inconsistency when compared to official guidelines on drinking in pregnancy from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antenatal care for uncomplicated pregnancies clinical guideline (CG62) retained previous advice that did not include the ‘no alcohol’ recommendation throughout pregnancy. In December 2018, NICE withdrew their previous guidance under section 1.3.9 of CG62 and added a link to the UK CMOs’ low-risk drinking guidelines.

The importance of consistent messaging has been identified as a policy priority[footnote 18] with advocacy groups raising concerns around the length of time the CMO advice did not align with that from NICE. The UK was slower than other countries in recommending no alcohol during pregnancy. The US Surgeon General has advised against consuming alcohol during pregnancy since 1981.[footnote 19]

There is a lack of data for how many people know the correct advice for no alcohol during pregnancy, likely exacerbated by the message inconsistency. However, a recent question incorporated into a nationwide survey by The National Organisation for FASD (then NOFAS-UK) has yielded some useful data.

NOFAS-UK survey question

In early 2019, NOFAS-UK commissioned a polling organisation to include a question on awareness of the recommendations for drinking during pregnancy. The polling was conducted nationally across 12 regions, with a sample size of 2,000 across a wide demographic range.

Table 2: NOFAS-UK survey question on CMO guidance – responses to the question: ‘Which of the following do you think is the correct UK CMOs’ guidance to women who are pregnant or planning to become pregnant?’

| Choice | % (n = 2,000) |

|---|---|

| Avoid drinking alcohol in the first 3 months of pregnancy and if you choose to drink have no more than 1 to 2 UK units once or twice a week and avoid getting drunk or binge drinking | 10.6% (212) |

| Avoid drinking alcohol in the first 3 months of pregnancy and if you choose to drink have no more than 5 to 6 UK units once or twice a week and avoid getting drunk or binge drinking | 5.0% (99) |

| The safest approach is not to drink alcohol at all | 76.2% (1,523) |

| It is safe to drink any amount of alcohol | 2.6% (52) |

| None of the above | 5.7% (114) |

Overall, around three-quarters (76%) of respondents selected the correct answer (table 2). If we analyse the responses as being either correct or incorrect, then knowledge of the correct guidelines was associated with age and gender. These patterns showed statistical significance (that is, the chance of these associations being by chance are very low, both less than 1 in 1,000); a greater proportion of women were aware (p < 0.001), and older age groups had a higher proportion of correct responses (p < 0.001) (see figure 2).

Reasons for these differences between age groups are unclear. There may be other factors not covered by the survey that explain the link, for example socio-economic status, although we cannot be sure. If the effect of age is genuine, possible reasons might be better awareness of official guidance in older groups, or greater experience of older people around the problems caused by alcohol during pregnancy.

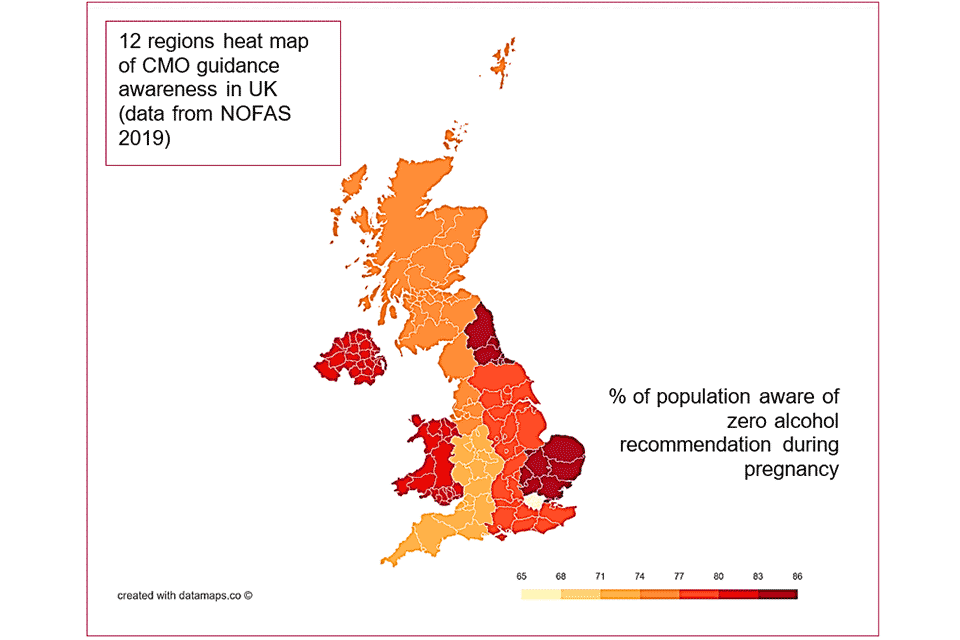

Across the 12 regions, London had the lowest awareness with only 66.2% of people answering correctly. East Anglia and the North East had the greatest proportion answering correctly at 83.6% and 85.4% respectively (see figure 3).

These results should be treated cautiously as they come from a single survey question, and the regions are large. Nevertheless, they provide some modest evidence of a problem of awareness, as the youngest (and most likely to become pregnant) age groups have the poorest understanding that alcohol should be avoided in pregnancy.

Figure 2: proportion of respondents selecting the correct CMO guidance to abstain drinking alcohol during pregnancy

| Age bracket | % answering correctly |

|---|---|

| Age 18 to 24 | 67.14 |

| Age 25 to 34 | 64.81 |

| Age 35 to 44 | 70.09 |

| Age 45 to 54 | 79.89 |

| Age 55+ | 84.44 |

The highest proportion selecting the correct recommendation are ages 55+ followed by 45 to 54. The lowest proportion selecting the correct recommendation are ages 25 to 34 followed by 18 to 24. Number of respondents: 2,000.

Figure 3: the proportion of the population that is aware of the UK CMO low risk drinking guidelines to abstain from drinking alcohol during pregnancy in the UK’s 12 regions

Data from figure 3:

- London (65% to 68%)

- South West (71% to 74%)

- West Midlands (71% to 74%)

- North West (74% to 77%)

- East Midlands (77% to 80%)

- South East (77% to 80%)

- East Anglia (83% to 86%)

- North East (83% to 86%)

- Scotland (74% to 77%)

- Wales (80% to 83%)

- Northern Ireland (80% to 83%)

Policy context

Advocacy groups

All Parliamentary Group for FASD

An All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) set up in 2015 aims to address the issue of FASD in the UK and to enable Members of both Houses of Parliament to have a platform from which to encourage debate and influence policy. The group also seeks to raise awareness of FASD, contribute to a reduction in the prevalence of the condition, and works to establish appropriate support mechanisms for those affected by FASD.

The group commissioned a report, published in 2015, to investigate the current picture of FASD in the UK.[footnote 20] This gathered oral and written contributions from key stakeholders across the country, delivering 12 recommendations. The group is currently chaired by Bill Esterson MP, who has raised parliamentary questions and led an adjournment debate in the House of Commons.

The National Organisation for FASD (formerly NOFAS-UK)

The National Organisation for FASD are a national FASD charity in the country supporting those with FASD and their families. They provide a national helpline to family members or carers of children with FASD, as well as providing advice to midwives and medical professionals. They currently serve as the secretariat for the APPG.

They have a strong social element, organising wellbeing events where people can share experiences and create support networks, as well as a social media presence.

The National Organisation for FASD also provide professional training through online courses, resources and in-house training sessions to public and private organisations. Their reach extends to GPs and midwives, but also non-healthcare professionals such as those from the school and prison services.

They are active in political advocacy and amplify the voices of those living with FASD ensuring their stories are heard.

FASD UK Alliance

The FASD UK Alliance is a coalition of groups active in the field, with the stated objective of achieving social change for those affected by FASD. The alliance consists of a diverse range of groups representing local, regional and national groups, as well as links internationally.

The FASD UK Facebook group is jointly monitored by several leaders of the FASD UK Alliance groups. There are also other FASD UK online support groups for Professionals, and another on FASD and Gender Identity. The membership of the FASD Alliance continues to develop, but as of writing the organisations listed include:

- Centre for FASD

- CoramBAAF

- Hertfordshire & Area FASD Support Network

- ÉNDpae

- FASD Awareness

- Family Futures UK

- FASD Cymru

- FASD Devon and Cornwall

- FASD Dogs UK

- FASD Greater Manchester

- FASD Hub Scotland

- FASD Network UK

- FASD Scotland

- Living with FASD South West

- Much Laughter: Stand Up for FASD

- The National Organisation for FASD

- Oshay’s FASD

- FASD Fife

- Elucidate Training

- Peterborough/Little Miracles Family

- Support Group

- Red Balloon Training

- SEND Consultancy – Carolyn Blackburn

- Stoke and Staffordshire FASD UK

- UK and European Birth Mothers – FASD

National government

Throughout 2018 and 2019, the government has engaged in a series of activities to develop policy on FASD. During the autumn of 2018 the then DCMO, Professor Gina Radford, led 2 stakeholder events co-hosted with NOFAS-UK to discuss the latest evidence base, learn about current good practices, identify problem areas and consider options for the development of future policy.

The government position on the topic was put forward in January 2019 during an adjournment debate in the House of Commons.

In early 2019, DHSC asked NICE to develop a quality standard for the diagnosis and care of those affected, based on existing work from Scotland.[footnote 10]

In August 2019, funding to support work around FASD was made available as part of a wider policy programme aimed to tackle problems faced by children of alcohol-dependant parents (CADeP). This is a cross-departmental programme launched in April 2018, when DHSC and the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) announced joint funding of over £7 million. The projects also support work on the Parental Conflict programme being led by DWP, and complement existing work with families across other programmes in government. The programme consists of 3 major elements:

Innovation fund

Led by Public Health England, the innovation fund is a £5.5 million package of measures for local authorities to develop plans which improve outcomes for CADeP. Nine local authorities were selected for funding to implement projects running from 2018 to 2019 to 2021 to 2022.

Helpline

To further the support being made available for CADeP, £500,000 will also be invested by DHSC in 2019 to 2020 and 2020 to 2021 to expand an existing helpline. This will be run by the National Association of Children of Alcoholics (NACOA) who have a strong track record in this area.

Voluntary sector section 64 funding

DHSC and DWP have also committed up to £1 million to fund voluntary sector organisations for national capacity building under the section 64 grant scheme. Following a successful application and selection process, 3 organisations were selected and the projects are running over 2018 to 2019 and 2019 to 2020.

In 2019 a proportion of the voluntary sector section 64 funding was made available explicitly to support work around tackling FASD. Government guidance states that the aim of the call for bids is to “harness the creativity and capacity of the voluntary sector to improve outcomes for those living with FASD and their families, and to reduce the number of alcohol-exposed pregnancies”.[footnote 21] Five projects ran from 1 April 2020 until 31 March 2021 to prevent cases of FASD, raise awareness among professionals and front line staff and help improve support for those living with its consequences.

OnePlusOne: focus on prevention

The project aims to reduce the risks of FASD by improving the help available to couples, enabling them to find new ways of coping with stress, thereby reducing couple conflict and alcohol use during pregnancy through an online tool Just the one? Avoiding alcohol in pregnancy.

Seashell Trust and National Organisation of FASD: focus on raising awareness and support

The project provides training for professional to better meet the needs of children and young people with FASD. At the core of the project is the creation of a new Me and My FASD toolkit and Best Practices and UK Language Guide.

Aquarius Action Projects: focus on prevention, raising awareness and support

The project will delivers: 1:1 service for women with a history of substance misuse who are currently or likely to become pregnant in the near future. Awareness training for professionals and students about FASD. Developing an FASD pathway and network for relevant bodies. 1:1 and peer support for children with FASD and their family

Adfam: focus on raising awareness and support

The aim of the project is to train practitioners and working in partnership with local authorities to develop local pathways to diagnosis and peer support groups for families and children with FASD. The lessons of the work in the local authority areas will be distilled into a guidance document for all local authority areas on developing their FASD response.

FASD Network: focus on support

An evaluated FASD initiative to establish family support and training programmes. Developing a guidance to support newer agencies that may be created as FASD developments emerge in the UK.

Diagnosis and epidemiology

Complexity of diagnosis

Diagnosing FASD is complicated, and there is no specific test for the condition. Identification is through recognition of expected characteristics while ruling out the impact of other causes that may better explain the presentation. The defining features of FASD can be difficult to assess in new-borns. Getting a reliable history of pre-natal alcohol use can also be difficult as people will often have to rely on memory, and women may feel frightened and stigmatised by reporting alcohol use during pregnancy. For looked after children, there may be further challenges in obtaining knowledge of their birth mother’s alcohol consumption.

Diagnosis requires a medical evaluation and neurodevelopmental assessment performed by specialists from a range of disciplines.[footnote 22] The specialist centre in Surrey includes a range of professionals, including:

- speech and language therapists

- clinical psychologists

- consultant psychiatrists

- advisory input from occupational therapists

Each of the different categories of FASD (that is, partial fetal alcohol syndrome (pFAS), alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND) and alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD)) can be diagnosed by a set of diagnostic markers.[footnote 12] However, classification of the terms has been changing as academics and clinicians around the world develop the evidence base. Currently, the National Institute of Health (NIH) via the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) is sponsoring an international approach to develop research diagnostic criteria for FASD. The recent quality standard produced by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), based on the Canadian 2016 update, simplifies these terms by referring to FASD either with or without ‘sentinel facial features’. NICE have accepted the SIGN 156 guideline so these terms are now the guidelines for England as well.

As yet, no single set of guidelines for diagnosis have achieved consensus in the academic community, although there is a lot of agreement on the main principles. Differences in guidelines are found in measurement of facial features, growth, criteria for assessing neurodevelopment and the approach to confirming pre-natal alcohol exposure.[footnote 22] A recent study compared 5 different approaches to diagnosing FASD.[footnote 23] While recognising that the core features were consistent across each diagnostic approach, it suggested that agreement in diagnosis across the FASD spectrum using these different approaches was only ‘fair’ to ‘moderate’ related to sensitivity and specificity of each approach. The authors concluded that there were problems with the validity of these methods when compared with one another (‘convergent validity’). As the discourse on nomenclature has developed, the literature highlights some concerns, arguing for example that some approaches may mix up risk factors with causal factors.[footnote 24]

Nevertheless, consensus is beginning to emerge around the optimal diagnostic path, although a range of approaches are still used. The guidelines developed by the Canadian Advisory group on FASD have emerged as the leading authority for diagnostic guidance, developed initially in 2005 and revised in 2016.[footnote 22] However, the upcoming NICE Quality Standard is based around the Scotland SIGN 156 standard.

The 2019 SIGN guidance lists the range of expertise required to obtain a diagnosis:

-

neonatologist, paediatrician or physician with competency in assessment of FASD

-

child development specialists with the skillset to conduct physical and functional assessments (for example, speech and language therapist, occupational therapist, clinical psychologist, educational psychologist)

With an extensive list of others who may offer input to the diagnostic process:

parents and carers, advocates, childcare workers, clinical geneticists, cultural interpreters, family therapists, general practitioners, learning support, mental health professionals, mentors, nurses (for example, school, learning disability, and so on), neuropsychologists, probation officers, psychiatrists, social workers, substance misuse service staff, teachers and vocational counsellors.

Source: SIGN 156, page 25.

It is clear that a highly multi-disciplinary approach is required; however, most of the necessary skills should be available in the community. Ensuring access to these skills means there is a need to develop the right systems which are effectively resourced.

Importance of early diagnosis

Early diagnosis of FASD creates better opportunities to intervene earlier and reduces the rate of secondary disabilities and issues such as exclusion from school. It also reduces the risk of future alcohol-exposed pregnancies.[footnote 25]

The literature also suggests that obtaining a diagnosis is important from the perspective of the individual and their families, providing relief and validation as parents understand their children’s challenges,[footnote 26] and it is perceived as a necessary step to obtain support from the system.[footnote 27] Nevertheless, it is important to recognise that a diagnosis can also bring feelings of guilt for the family, and the process of obtaining the diagnosis can be a significant source of stress and anxiety.[footnote 28]

Receiving an early diagnosis can reduce the chances of adverse life outcomes.

Diagnosis remains important even beyond childhood, although this can be difficult to obtain. Obstacles to diagnosis include lack of reliability in distant personal histories, the small number of specialists with the training and experience necessary[footnote 29] and lessening of facial features with age. Although opportunity for early intervention may have been missed for these individuals, a valid diagnosis can still remove barriers to treatment services and benefits as well as help understand the difficulties they have been facing in their lives.

These narratives were reinforced from the experiences recounted at the deputy CMO roundtable events in 2018, where 6 people shared their stories of trying to access diagnosis, support and services; the importance of receiving a diagnosis, and the effects of misdiagnosis are recurrent themes.[footnote 30] Without a diagnosis, individuals may be unable to access the support available to those with other neuro-developmental conditions such as autism. Even if the diagnosis is made, problems can persist as services are often described as being for those with learning disabilities and autism. People with FASD may not fit the necessary criteria for access as currently exists.

FASD surveillance

Although passive surveillance systems can be used effectively for conditions that are straightforward to diagnose, it is not viable to rely on them to obtain prevalence figures for FASD. This is due to the difficulty in reliably diagnosing FASD, limited awareness of FASD among healthcare professionals, and the level of training required to make a formal diagnosis.[footnote 31]

The current global standard for disease reporting is the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Disease, 10th version (ICD-10); FAS is indicated by code Q86 and FASD does not have a code. This creates difficulties for reliability of data acquisition. ICD-11 contains a term for neurodevelopmental disorders associated with pre-natal alcohol exposure.

Similarly, different coding methods in the UK have inconsistent approaches that add further complexity to diagnosis recording and surveillance. We have historically relied on a range of coding methods in primary and secondary care in England. The move to a unified SNOMED CT system from 2018 may present an opportunity to improve consistency, as it contains a code for FASD. However, there are also other codes that might be applied by clinicians, especially if no formal diagnosis of FASD has been made.

Estimates of prevalence

Challenges in diagnosis and data collection make it difficult to obtain reliable estimates of FASD prevalence in England. To date, there are no prevalence studies, making it difficult to understand the level of need and potential commissioning requirements. The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) commenced a study in 2018 to ascertain the prevalence of FAS across the UK through passive surveillance, but it is not investigating FASD. It is being run by the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU).

Under-reporting of the condition is a well-recognised problem. In an analysis comparing regional hospital admissions over time, an increase in alcohol related admissions in women of childbearing age was not associated with an increase in admissions for FASD related conditions. The study authors concluded that there is significant under-reporting of FASD.[footnote 32]

The first national effort to quantify FASD in the UK was published late 2018.[footnote 33] The study found a screening prevalence range in the UK of 6% to 17%. It relied on a data set from the ALSPAC cohort (children born around Avon in the 1990s), applying diagnostic criteria retrospectively. The study acknowledges limitations from this approach, and it important to recognise that screening prevalence may be significantly higher than actual prevalence in the wider population. Nevertheless, the results indicate a potentially very significant burden in the population. It strengthens the case for prioritising robust studies to estimate UK prevalence.

A prevalence study in primary schools in Greater Manchester began in 2019, led by the University of Salford. This was the first UK active ascertainment study, which is the most reliable approach to assessing prevalence. Unfortunately, the study was cut short because of COVID, at which point data were available for 3 schools. In these 3 schools, 1.8% of children had FASD. At the time of writing the prevalence study was accepted for publication and should be out in e-version shortly.

There are currently no prevalence studies for FASD in the UK

There are also some local examples of smaller studies and local audits, for example an audit conducted in Peterborough in 2013.[footnote 34] Community paediatricians conducted this audit from April 2010 to August 2013, counting the number of children seen with a clear history of pre-natal alcohol exposure, and looking at how many might have FAS/FASD. Although they used Canadian Criteria (as described by Chudley et al in Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Canadian guidelines for diagnosis) to diagnose FAS, and the same criteria without facial features for FASD, resources for gold-standard diagnosis were unavailable.

During the period, they identified 72 children with FAS/FASD, estimated at around 3% of the children seen over the period. This rose to around 27% for looked after children. During the audit there was ongoing staff training around the issue, and the identification of at-risk children steadily increased. These findings suggest that improving awareness and training may improve identification. This was a retrospective audit, and the findings are not necessarily generalisable, but it is still instructive to get a sense of the level of need, and the challenges of quantifying it accurately.

The Educational and Child Psychology team at Oldham Council conducted an informal local FASD audit and are currently writing the findings for publication. The primary schools involved in this audit agreed to be part of the study and the records/ SEND lists used and interrogated by the EPs were anonymised. Recognising the challenges outlined above, they explored alcohol use where it is known to have impacted family life more generally, using a questionnaire to tally against known special educational needs across some of the primary schools in Oldham. Although the generalisability of findings from studies such as this is limited, activities of this type could be encouraged at a local level to build a clearer picture of health needs among geographic communities.

A regional Health Needs Assessment was conducted in 2016 for North East England, led by Public Health England, in response to the North East FASD Champions Network.[footnote 35] This drew on expertise from a wide range of stakeholders, and made recommendations around data quality and communication, stigma, care pathways, and awareness and training. Acknowledging challenges and limitations of the data it used, it nevertheless provided a reliable source for further research and service development in the region.

Global prevalence data

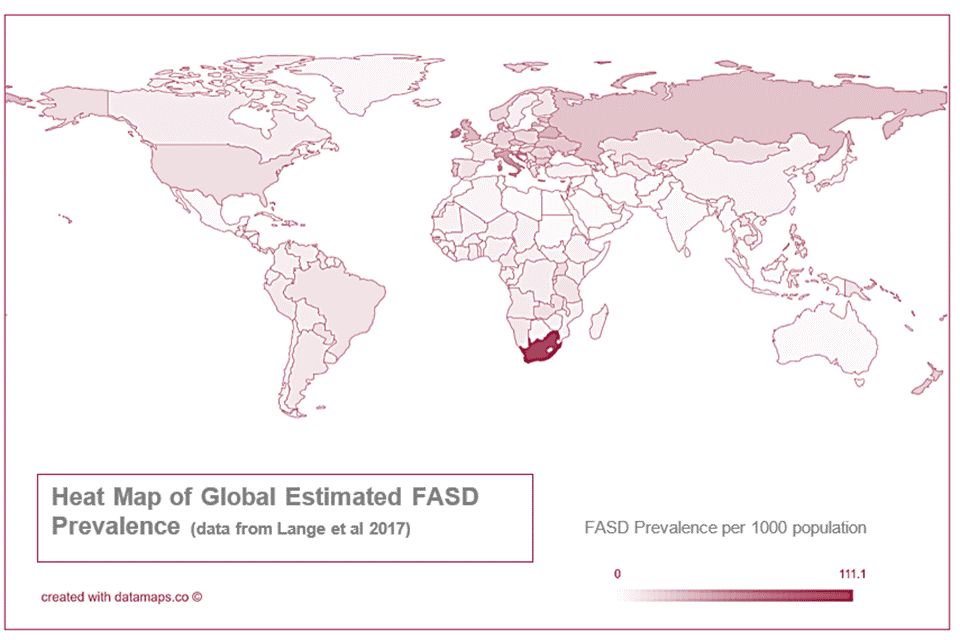

The global situation was described in a systematic review and meta-analysis that utilised data from 187 countries.[footnote 7] It found a prevalence of 7.7 per 1,000 population globally, with large regional differences. The WHO European region was significantly higher than anywhere else, at 19.8 per 1,000. Figure 4 gives an overview comparing prevalence in countries globally.

The United Kingdom was estimated at 32.4 cases per 1,000 population (3.24%, 95%CI 2% to 4.9%). The study acknowledges limitations, as countries that had zero or one prevalence study relied on self-reported alcohol consumption measures. This approach is vulnerable to bias as memory and honesty in reporting may tend towards an underestimate of the problem.

Figure 4: estimated global FASD prevalence

The highest estimated prevalence is in South Africa, followed by the European region, most prominently Eastern Europe, the UK and Italy. The lowest estimated prevalence is in North Africa and the Middle East.

The figure of 3.24% has been cited as part of the programme of work undertaken by the Greater Manchester Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies programme. For example, as part of their regional estimates, the data analytics team applied the prevalence estimate to the population of Greater Manchester and the surrounding areas, leading to an estimate of around 90,000 people potentially affected of a population of 2.7 million in the Greater Manchester area.

Although these types of estimates can be a useful indicator of the potential extent of the problem and possible unmet need, it is clear that policy-makers and providers in the United Kingdom would benefit from access to reliable prevalence estimates to inform their work.

Recent data estimating differences between subpopulations globally make it clear that FASD disproportionately affects disadvantaged groups, exacerbating health inequalities. The groups include children in care, correctional, special education, specialised clinical and Aboriginal populations.[footnote 36]

Need for prevalence estimates

The lack of reliable prevalence estimates for England and the UK present a significant barrier to understanding and meeting the needs of those living with the condition, their families and carers. Until this is resolved it will remain difficult for service commissioners to plan for and provide the appropriate level of services for diagnosis and support.

This issue has been recognised by the British Medical Association, and the 2015 report from the APPG on FASD [footnote 20] called for an urgent UK population-based prevalence study to inform prevention efforts and policy development.

Relying on passive surveillance has significant limitations, and so active case ascertainment studies are needed to give a clear picture of FASD in England.

There is an immediate need for wider UK population-based estimates of FASD prevalence, using active case ascertainment studies.

Prevention and management

FASD is a complex, multi-faceted health problem, and it is necessary to take a wide-ranging approach to prevention.

In practical terms, preventive approaches are based on the principles of reducing the number of women consuming alcohol during pregnancy, and the provision of appropriate care and support services for those with FASD and their parents/carers. Further to this, FASD prevention should complement public health approaches to family planning and contraception. Resources from NHS Scotland classify prevention under 3 categories:[footnote 37] primary, secondary and tertiary:

-

primary prevention – broad population efforts designed to raise awareness about the risks of alcohol-exposed pregnancies

-

secondary prevention – targeted screening, counselling and interventions with women seen as being in, or at risk of, alcohol-exposed pregnancies

-

tertiary prevention – highly targeted work with the aim of minimising the likelihood of another pregnancy resulting in FASD

Efforts to reduce alcohol consumption across the population are likely to play an important part in reducing alcohol-exposed pregnancies, for example through improved alcohol labelling, minimum unit pricing, alcohol use screening and so on, though full exploration of these issues are beyond the scope of this document.

There is ongoing research to better understand genetic and epigenetic factors that contribute to determining drinking patterns,[footnote 38] and potential for targeting those at higher genetic risk.[footnote 39] However, there are relatively few studies looking at the genetic determinants of moderate alcohol consumption, and none specifically in relation to FASD and lower levels of alcohol intake. Although this research shows promise, with more likely to be done in future, for now this approach to prevention is of limited value.

This section will first consider approaches to risk assessment for alcohol-exposed pregnancies, before looking at different approaches to preventing and managing FASD.

Risk assessment for alcohol-exposed pregnancies

Apart from FASD with sentinel facial features, diagnosis of FASD requires a positive finding for maternal use of alcohol during the pregnancy. The primary method of getting this information is to rely on self-reporting by the mother and the family. However, the social sensitivity around the issue means this is often unreliable and can lead to under-reporting. Inaccurate self-reports of drinking may occur for a range of reasons, such as social stigma.[footnote 40]

Research continues in understanding the range of ‘biomarkers’[footnote 41] that could identify alcohol use, categorised under:

- clinical

- molecular

- omic

- imaging

- meconium

- cord blood

- anatomical

- neurobehavioral biomarkers

These may in future play an increasingly important role in ascertaining the risk of alcohol exposure, potentially identifying highest risk populations. This could help to make decisions on how and whether to target preventive interventions.

For example, one recent study from Scotland analysed the meconium (faeces) of new-borns, and identified markers of pre-natal alcohol consumption in 42% of samples studied.[footnote 42] Although the study had significant limitations, it did provide evidence that there tends to be under-reporting of alcohol use during pregnancy. It also demonstrated that this form of analysis is viable to obtain estimates of pre-natal alcohol use in a population.

However, it is important to recognise that obtaining diagnostic data such as this carries ethical and potentially legal risks.[footnote 43] These are considered in more detail in the section below, Law and Ethics.

More commonly, pre-natal alcohol use is identified through verbal or written history taking in a clinical setting, despite the limitations of this approach. Where this is recorded in maternity medical records, it should ideally be automatically transferred to the child’s records to prevent the information being lost. This is particularly important for the population of looked after children.

Screening tools

To assess the risk of pre-natal alcohol use, questionnaire style screening tools can be deployed along the maternity care path. Public Health England provides guidance on the use of a range of alcohol screening tests,[footnote 44] which can be utilised during the maternity care pathway to identify those who are drinking alcohol, at which point an appropriate intervention can be deployed if needed.

For example, AUDIT-C is a 3-question alcohol screen that can help identify individuals who are hazardous drinkers. It includes the following questions:

1. How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?

- never (0 points)

- monthly or less (1 point)

- 2 to 4 times a month (2 points)

- 2 to 3 times a week (3 points)

- 4 or more times a week (4 points)

2. How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day when you are drinking?

- 1 or 2 (0 points)

- 3 or 4 (1 point)

- 5 or 6 (2 points)

- 7 to 9 (3 points)

- 10 or more (4 points)

3. How often do you have 6 or more drinks on one occasion?

- never (0 points)

- less than monthly (1 point)

- monthly (2 points)

- weekly (3 points)

- daily or almost daily (4 points)

Another option that has been deployed in a secondary care setting in England[footnote 45] is the TWEAK screening tool to identify people at risk of harmful drinking. There is some evidence that it is an effective tool, although results appear to vary depending on cultural context.[footnote 46], [footnote 47], [footnote 48]

TWEAK is a 5-item scale for harmful drinking in pregnancy and is an acronym for the questions below:

1. Tolerance – How many drinks does it take to make you feel high?

2. Worry – Have close friends or relatives complained about your drinking in the past year?

3. Eye opener – Do you sometimes take a drink in the morning when you wake up?

4. Amnesia – Has a friend or family member ever told you about things you said or did while drinking that you could not remember?

5. Kut down – Do you sometimes feel the need to cut down on your drinking?

Audit-C and TWEAK have been found in studies to have limitations. Other evidence-based research indicates that brief interventions, including motivational interviewing, may be most productive. Equally, alternative questions can help. For example, one study found that using the question “Since you’ve been pregnant, have you had any special occasions?” can open important dialogue. Another study found that women at risk of an alcohol exposed pregnancy were identified by asking a question about single binge drinking episode. [footnote 49], [footnote 50], [footnote 51]

Principles of reducing alcohol-exposed pregnancies

Although we still lack a reliable prevalence estimate, the United Kingdom is estimated to have the 4th highest rate of drinking during pregnancy in the world.[footnote 4] The prevalence of drinking during pregnancy differs between countries and individual studies, for example 6% in Sweden, 10% in the United States, 54% in Ireland, and 71% in Denmark.[footnote 40]

In some instances, consumption of alcohol during pregnancy may be attributable to a lack of awareness of the zero-alcohol recommendations. At other times drinking may occur despite warnings from clinicians and public health campaigns. For unplanned pregnancies, women may continue to drink as they are unaware that they are pregnant.

A systematic review in 2011 identified 14 studies assessing the factors associated with prenatal alcohol use.[footnote 40] It concluded that the most important factors that predicted prenatal alcohol use were the quantity and frequency that women would typically drink pre-pregnancy, and exposure to abuse or violence. This suggests that broader public health approaches to alcohol consumption may be of benefit, alongside national and local efforts to end violence against women.[footnote 52]

A scoping literature review in 2019 charted interventions and their distribution globally. It identified 32 prevention and 41 management FASD interventions. The vast majority, 61, were from North America. Despite having among the highest prevalence of FASD, only 3 studies were identified from Europe.[footnote 53]

Behaviour change and determinants

Behaviour change is seen as a core component of many prevention approaches, since if alcohol is not consumed during pregnancy then FASD cannot occur. Developing effective interventions that meet the needs of at-risk mothers requires an understanding of behaviour and its determinants.[footnote 54]

An extensive discussion of this issue is beyond the scope of this report, but it is important to appreciate the concepts underpinning this theory. Merely providing information to an individual is often not enough to engender a positive change in behaviour. This is because a person’s freedom to make choices is often affected, constrained or ‘determined’ by a host of other social factors outside of their control.[footnote 55] An individual’s set of beliefs and behaviours are influenced by these social factors, often referred to as ‘psychosocial determinants’. In the context of alcohol-exposed pregnancies, this means considering issues such as an individual’s perception of social norms around drinking, feelings of stress relief from drinking, and access to services that can reinforce key health messages.[footnote 54], [footnote 56]

Successful behaviour change interventions thus need to alter or work with these psychosocial determinants to enhance the autonomy of an individual and increase the chance of an intervention bringing about a positive change in their life.[footnote 57]

There are a range of interventions utilising principles of behaviour change that are supported by evidence of effectiveness from around the world,[footnote 53] using approaches such as motivational interviewing, peer-led multimedia presentations, web-based intervention, and training for alcohol servers on responsible beverage service.

There is evidence that a wide range of effective interventions can be deployed in healthcare setting, schools and the community.

Contraception and reducing unplanned pregnancies

Empowering women to have greater control in planning for pregnancy is an important aspect of reducing the number of alcohol-exposed pregnancies. Health professionals can take the opportunity to raise the issue of contraception and family planning with all women of childbearing age, and make clear the links between alcohol, sexual activity and FASD. The alcohol screening tools can help to understand what types of intervention might be most appropriate and whether brief advice or referral to specialist or family planning services is needed.[footnote 37]

CHOICES is a behavioural intervention for women who are not pregnant, but are at risk for an alcohol-exposed pregnancy (AEP). Originally an acronym, Changing High-Risk Alcohol Use and Increasing Contraception Effectiveness Study, this is no longer spelled out. It uses motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural strategies to increase women’s motivations and commitment to change. The programme includes 2 to 4 counselling sessions, plus a contraceptive counselling session.[footnote 58] There is a sound evidence base, with efficacy shown through a series of randomised control trials in a range of settings.[footnote 59] An intervention loosely based on CHOICES is currently being trialled as part of the Greater Manchester Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies programme. Since July 2019, 1028 people have been identified as being at risk of an AEP, with 67.2% (691) engaging with a prevention intervention. Of those who are identified as at risk, 18.3% (189) reduced alcohol consumption. Throughout the programme, LARC uptake in prevention services has always stayed at a relatively small level, with 1.7% (17) people taking up a LARC offer. To eliminate data lags and due to the process of reporting data changing in the autumn of 2019, Table 3 takes a sample of data from January to December 2020.

Table 3: data from Greater Manchester Alcohol Exposed Pregnancy programme

| Metric | Total % | Total number | Monthly average |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women who have been identified as at risk of an AEP | N/A | 524 | 43.6 |

| % who were identified as at risk of an AEP who then engage with prevention intervention | 64.5% | 338 | 28.2 |

| % who were identified as at risk of an AEP who then reduce alcohol consumption | 20.6% | 108 | 9.0 |

| % who were identified as at risk of an AEP who are in receipt of a LARC | 0.95% | 5 | 0.5 |

524 women as at risk of an AEP were identified and 64.5% engaged with prevention intervention and 20.6% of those reduced their alcohol consumption. 0.95% of women identified as at risk of an AEP are in receipt of a LARC.

Nationwide approaches to prevention

Maternity Transformation Programme

The Maternity Transformation Programme brings together a wide range of organisations to improve maternity services across England, seeking to achieve the vision provided by the 2016 report Better Births.[footnote 60] The programme is delivered across 9 work streams led by a programme board and representative stakeholder group.

Public Health England leads on workstream 9, improving prevention – this includes a focus on supporting a reduction in the proportion of women drinking alcohol during pregnancy. PHE in partnership with Tommy’s, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and the UCL Institute for Women’s Health, has created [Planning for Pregnancy](https://www.tommys.org/pregnancy-information/planning-a-pregnancy’, a digital tool to help with this. Additionally, Start4Life has been developed as part of PHE’s social marketing work.

Health Education England have also developed online resources, with a ‘Substance Misuse During Pregnancy’ component of the Healthy Child Programme module. This training is free to use for all NHS staff.

DHSC is currently working in partnership with a range of charities such as Sands (the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death charity), and other organisations including NHS England, Public Health England, the Royal College of Midwives and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. They will take forward the National Maternity Safety Strategy, a programme of work to raise awareness of risk factors among pregnant women and health professionals. This will ensure advice is consistent on minimising risk of still birth, promote healthy behaviours, and signpost where to go for help when needed.[footnote 61]

Alcohol labelling

In March 2017, DHSC issued guidance to the public and industry setting out how the UK CMOs’ low risk drinking guidelines can best be communicated on the labels of alcoholic drinks to the public including avoiding alcohol in pregnancy.

An increasing number of product labels reflect the CMO guidance, and work is on-going to extend this across the industry. Under retained regulation, information on labelling is not mandated for alcoholic drinks under 1.2% alcohol by volume (ABV). Nevertheless, voluntary participation means that some producers are still including the guidance. A public consultation on mandating more consumer information on alcohol labels is to be launched this year.

Management of FASD

Currently, there is no universally accepted framework for the clinical management of FASD, and more research is needed to understand different management approaches.[footnote 13], [footnote 62], [footnote 63] Further complexity arises from co-occurring conditions, such as ADHD, which may necessitate the use of other specific clinical strategies,[footnote 64] for example using medication to control symptoms.

Work from NICE on adopting the SIGN Quality Standard for FASD[footnote 10] should go some way towards building consensus, as it recognises important general principles around assessment and diagnosis that maximise the chances of success; when an effective plan of care is implemented, it should create adequate scaffolding for people with FASD to flourish. This means supporting children and adults with their limitations, and creating opportunities to utilise their strengths.

Individuals with FASD are all unique in how the condition affects their cognitive function, and the social impacts it has on them, their families and carers. It is important therefore to take an individualised approach.[footnote 10], [footnote 64] Effective treatment and management means correctly understanding the needs of the individual through appropriate testing and interpretation. Neurocognitive testing can play an important role in identifying strengths and concerns.[footnote 65] This should supplement a client and family-centred approach that recognises barriers unique to the individual.

Early on, this may be focussed on family and learning environments. For example, different components of FASD are being managed through programs such as the Alert Program for Self-Regulation for sensory issues [footnote 66] and MILE (Math Interactive Learning Experience Program) for education in mathematics.[footnote 67], [footnote 68]. There is on-going research in to parenting interventions; Salford University have commenced completed a study funded by the Medical Research Council trialling a parenting intervention. Preliminary results are promising, and the team is currently applying for funding for a larger scale trial due to conclude in 2020. Evidence for family-based interventions is becoming well established with a range of successful approaches reported.[footnote 69], [footnote 70], [footnote 71]

For adolescents and adults, the priority is likely to become finding employment opportunities that allow them to use their skills and talents, and giving help where they have difficulties. Systematic reviews have emphasised the importance of developing interventions across the lifespan.[footnote 53], [footnote 72]

In policy terms, this is a significant challenge. It needs a multi-sectoral approach that includes education, criminal justice and industry. A recent study from South Africa (where the prevalence of drinking during pregnancy is very high), proposed guidelines [footnote 73] that cited the following principles of policy development for FASD:

-

being culturally diverse

-

being collaborative, evidence-based, multi-sectoral

-

addressing social determinants of health contributing to FASD

As listed earlier in the document, there are a range of voluntary sector organisations around the country with interest and willingness to facilitate developments commensurate with these principles, and previous recommendations from the BMA and APPG for FASD.

Supporting the individual means understanding their particular strengths and limitations, and a deep understanding of the unique context of their life.

Services

Currently, provision of services for diagnosis and support of FASD is limited across England. There is a national specialist clinic in Surrey and Borders Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, with a new private clinic The Centre for FASD in Ipswich, Suffolk.

Provision of services is the responsibility of CCGs across the UK.

Proposed model of services

In 2014, the FASD Trust sponsored a meeting of healthcare professionals to provide the outline of a service structure for FASD services in the UK. The BMA[footnote 13] subsequently recognised the value of this approach for England, although stating changes may be necessary for the devolved nations’ health systems.

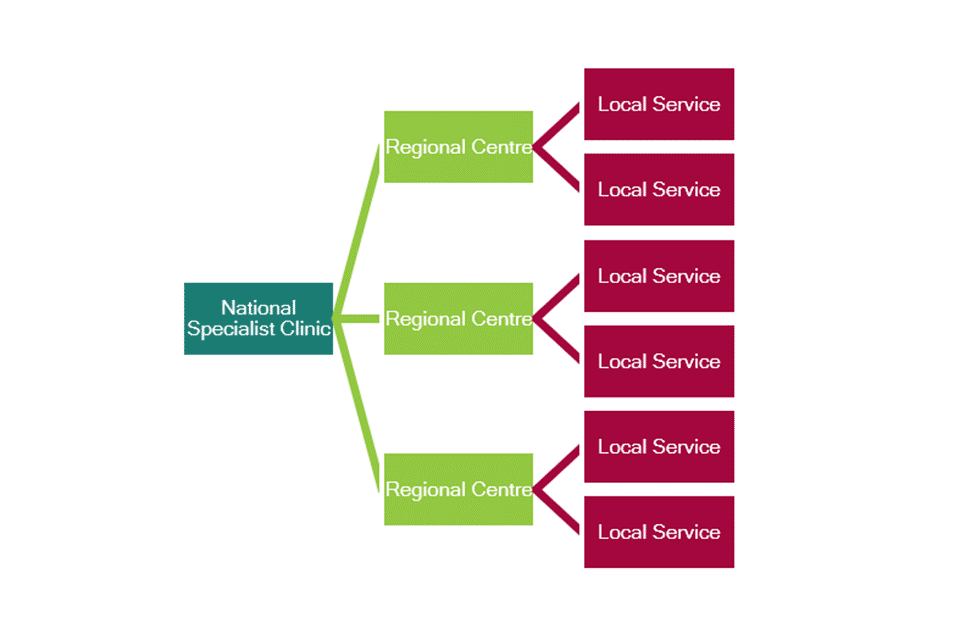

They proposed a hub and spoke model (see figure 5) with a single national specialist service, and multiple regional clinics around the country that have the necessary expertise to diagnose straightforward cases. This model builds capacity to manage the majority of simpler cases locally, escalating only the most complex.

A lack of expertise and confidence could prevent practitioners from developing skills. This model frees time for central expertise and supervision to be offered at appropriate levels and helps develop a more widely distributed skills base over time.

Eventually, it is envisioned that the national service could become the regional centre for the area where it is located as expertise embeds itself across the country. There would always be the need, in a resource restricted environment, to have access to more specialist assessment, but eventually this would be best served linked to a local and regional level. In the early stages however, the 3 tiers are likely to be required.

Related work also mapped out the proposed pathway for perinatal care and follow up for those with a high risk of AEP, but without clear diagnostic features of FASD.[footnote 74]

Figure 5: potential national service structure

Figure 5 shows: one national specialist clinic to lead on FASD services, to see the most complex cases and provide clinical advice. Regional clinics around the country to diagnose more straightforward cases. Local services to manage most straightforward cases locally and escalate cases if necessary.

National clinic for FASD

Currently, the specialist clinic sees cases of varying complexity. It is envisioned that in future it should see only the most complex cases, and provide clinical advice to the regional clinics. Initially this would be done routinely to develop expertise, but then eventually only when required as the skill base is established.

Funding for patients to visit the national clinic currently requires an individual funding request (IFR) to be approved by a CCG. This necessarily creates challenges for the sustainability of the clinic. IFRs cannot become routine, as they are designed only to cover exceptional circumstances. To make the service viable long term, a coherent approach to commissioning is required at the local level by CCGs and regionally by developing NHS structures such as the integrated care partnerships. Taking a collaborative approach over a greater area will allow support to develop while expertise grows.

Current inconsistency of referrals raises questions over the long-term sustainability of the specialist clinic. The lack of national expertise also means that less complex cases may end up being seen at the clinic, when local services may have been able to manage the case. These are issues that will need to be addressed as the service model evolves and grows.

Availability of services nationally

National FASD service commissioning survey

In May 2019, The National Organisation for FASD (then-NOFAS-UK) produced a report presenting the results of a series of Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to over 450 NHS trusts, health boards and other bodies across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.[footnote 75] Replies were received from 166 CCGs and 167 trusts. The authors recognised limitations to their approach but reported consistent feedback across the UK. NOFAS-UK highlighted a range of key findings in their report (see box below).

Commissioning survey key findings as reported by NOFAS-UK

Funding and commissioning of services

-

None of the CCGs that have provided services have a policy for commissioning services specifically for FASD

-

Most trusts said they did not hold information on FASD services, and do not code post-diagnostic services for surveillance

-

21.7% of CCGs say they provide for the diagnosis of FASD in children

-

8.4% of CCGs say they provide funding for diagnosis in adults, and 4.2% of trusts say they can diagnose adults

-

13.3% of CCGs said they expect trusts they commission to provide education and training on FASD, and 24.6% of NHS trusts said that they provide this in some form

-

The vast majority of CCGs are not planning to hold any form of consultation on these issues

-

13.9% of CCGs have an FASD lead

-

18.5% of trusts said they provide post-diagnostic care for those with FASD

Prevention

-

Most trusts and CCGs regard FASD as a paediatric issue only, and few consider diagnosis and post-diagnostic services for adults with the condition

-

37.8% of CCGs said they expected maternity services to give prevention messaging consistent with the 2016 CMO guidance, and 42.5% of trusts said they provide such prevention education

Professional training, education and awareness

Understanding of FASD by professionals in the healthcare community is a key component of improving the prevention and management of FASD in the UK. A 2015 mixed-methods study drew data from a series of focus groups and 505 questionnaires with a range of healthcare professionals.[footnote 76]

The study identified: a lack of professional knowledge; perceived need for consistent guidance; perception of stigma; a questioning of the validity of FASD; and a recognition of the need for early intervention and better support services. 10% of those completing the questionnaire, including one midwife, felt that FASD was irrelevant to their specialty.

The study concluded that knowledge tended to be superficial, and the lack of understanding of how to advise mothers of affected individuals remains limited (in common with similar studies in other countries).

An ethnographic study in New Zealand considered professional attitudes towards FASD.[footnote 77] It identified different frames of reference by which healthcare professionals make sense of FASD, which has important implications for their clinical decision making. It suggests that personal, non-clinical experiences are influential in setting these frames of reference.

A recent study from Scotland also took a qualitative approach, aiming to identify more effective ways of delivering ante-natal screening and brief intervention.[footnote 78] It concluded that building trusting relationships between pregnant women and midwives could permit more positive conversations, and more honesty in disclosing alcohol habits. Further work around this issue would be beneficial.

Taken together, the emerging evidence around professional training and awareness is that care and support for those affected by FASD could be developed by addressing deficits in professional understanding of the condition. Qualitative research suggests that it is important to consider personal perspectives and relationships when developing our approach to education.

There is clear evidence of a need for more professional awareness and training, which should be sensitive to individual perceptions and experiences.

Quality standard

In January 2019, SIGN released guidelines 156, ‘Children and young people exposed prenatally to alcohol’.[footnote 10] This work is being used by NICE to develop a quality standard for England. Quality standards set out the priority areas for quality improvement in health and social care, and should facilitate the planning and delivery of services to improve outcomes.

As SIGN is an accredited body, NICE accepted the guidelines and are adopting the evidence and recommendations. As of writing, the new quality standard is due for release this year.

Examples of good practice

Greater Manchester Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies Programme

Launched in May 2019, the Greater Manchester Health and Social Care partnership invested £1.6 million in their Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies programme. This programme fits with the broader initiative to reduce the harm experienced by children and young people in Greater Manchester as a result of parental substance misuse.

The devolved health and care system in Greater Manchester will use the funds over a 2-year period as a ‘proof of concept’ to reduce alcohol-exposed pregnancies and ultimately eliminate new cases of FASD.

The programme operates across 2 foundation trusts, Pennine Acute Hospital Trust (PAHT) and Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care Foundation Trust, covering 4 of the 10 GM localities (Bury, Oldham, Rochdale and Tameside).

The programme has a strong emphasis on support for vulnerable women at increased risk, training and awareness raising, and improving intelligence through structured data collection and a regional prevalence study. The aims are:

-

raise public awareness of the harm associated with alcohol consumption during pregnancy and FASD through a GM awareness campaign

-

raise awareness among the health and social care workforce through system wide training

-

prevent alcohol-exposed pregnancies through evidence-based locality interventions prior to pregnancy

-

develop innovative approaches to preventing alcohol pregnancies, where evidence does not currently exist

-

increase the spread of universal alcohol screening, advice, guidance and brief interventions during pregnancy within antenatal pathways

-

develop specialist and enhanced support during pregnancy for vulnerable women in ‘increased risk’ cohorts

-

increase the availability of midwife-provided long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) for vulnerable groups at the point of discharge following delivery

-

establish Peer Support and Mutual Aid models to increase the likelihood of long term sustained recovery and/or future reduction of alcohol-related harm post-pregnancy

-

undertake a research study to establish the likely prevalence of FASD in Greater Manchester

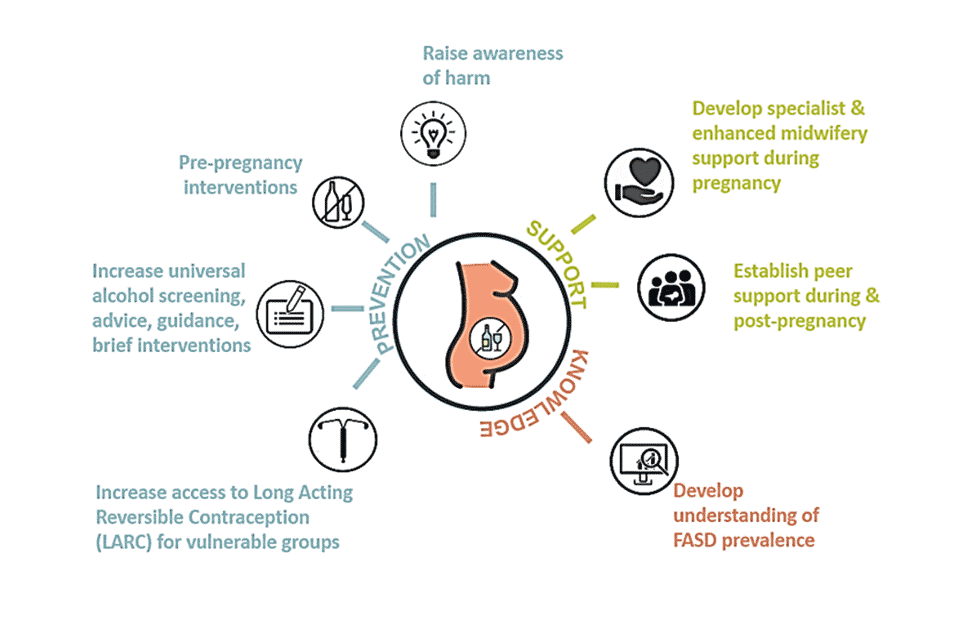

Figure 6: the Greater Manchester Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies Programme has 3 strands of work on prevention, support and knowledge

Figure 6 description

Prevention work includes:

- raising awareness of harm

- pre-pregnancy interventions

- increasing universal alcohol screening

- advice, guidance and brief intervention

- increasing access to LARC

Support work includes:

- developing specialist and enhanced midwifery support during pregnancy

- establishing peer support during and post-pregnancy.

Knowledge work includes:

- developing an understanding of FASD prevalence

Data metrics for the prevention element of the programme include the number of women identified at risk of an AEP, the proportion who receive an intervention, the proportion who reduce consumption to recommended levels, and proportion of those who attend a contraception appointment and are fitted with LARC.

All women seen by PAHT maternity services are screened for alcohol use through Audit-C, and receive an Alcohol Brief Intervention at first contact, at booking and at 36 weeks. Women who continue to drink during pregnancy are provided with enhanced support via specialist AEP midwives.

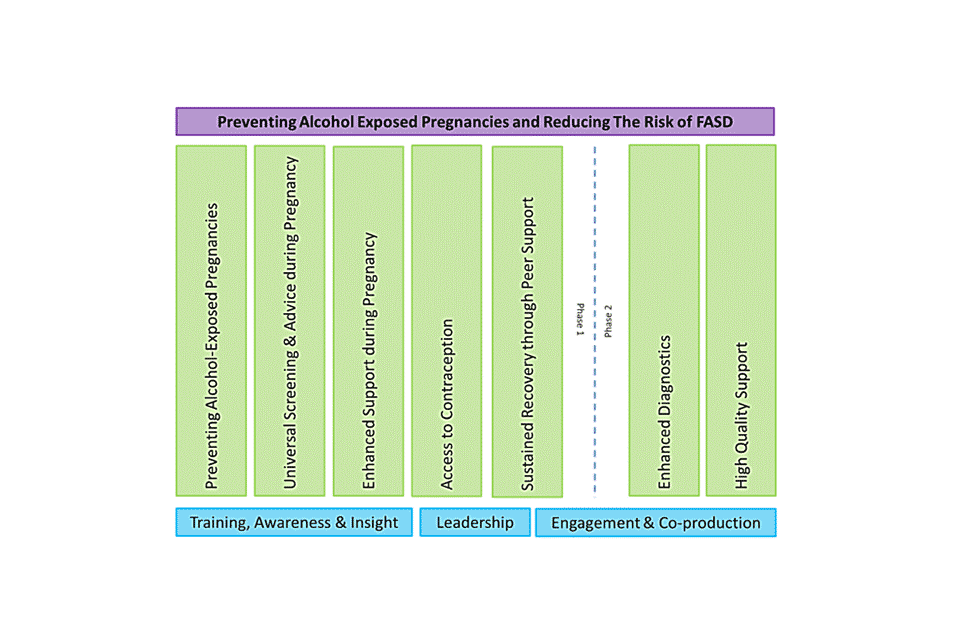

Figure 7: project map for Greater Manchester Alcohol Exposed Pregnancies Programme to reduce the risk of FASD

Figure 7 description

To prevent alcohol-exposed pregnancies, the following steps are followed:

- universal screening and advice during pregnancy

- enhanced support during pregnancy

- access to contraception

- sustained recovery through peer support

- enhanced diagnostics

- high quality support

Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care Trust: Maternal Alcohol Management Algorithm

Linked to the programme above, the Maternal Alcohol Management Algorithm (MAMA) Pathway is a novel approach to screening that aims to educate parents on the potential harms of alcohol during pregnancy. It was developed jointly between the Maternity Unit and the Hospital Alcohol Liaison Service (HALS) with support from The National Organisation for FASD and Lifeline (alcohol and drug service provider).

It identifies high-risk individuals to connect them with the health system for treatment and support, as well as assisting in diagnosis of FASD. Implemented from 2016, women are screened at their first appointment with the midwife using the TWEAK tool, repeated in the 16th week of pregnancy. Postnatal follow up aims to prevent return of harmful habits as well as working on helping to care for the new-born and preventing future alcohol-exposed pregnancies. Those at high risk can access the enhanced midwifery service for specialist support and onward referral to alcohol services as appropriate. The CQC has recognised this work as Outstanding Practice in their 2019 inspection report.[footnote 45]

MAMA allows routine data collection for surveillance purposes and to help track the long-term outcomes from alcohol-exposed pregnancies. It also provides robust evidence for those who need to investigate FASD as a possible diagnosis later in life.

Better Start Campaign